Kuznets’s Curse and a Cautionary Tale about the Power of Simplicity

Simon Kuznets invented modern GDP, or the way to measure the health of an economy using Gross Domestic Product. To explain further, as an economist he found a way to measure the production or output of a nation and track it as it went up or down. He came up with this idea during the Great Depression of the 1930s because he was concerned to measure how the country was recovering from the bust that followed the boom of the 1920s. He was later awarded a Nobel Prize for his work.

The huge benefit of GDP as a metric was that it summarised, in one number, the economic strength of the entire nation. By the end of World War II GDP had become the standard metric used by economists across the globe, to measure the economic health of an economy.

Very clever stuff.

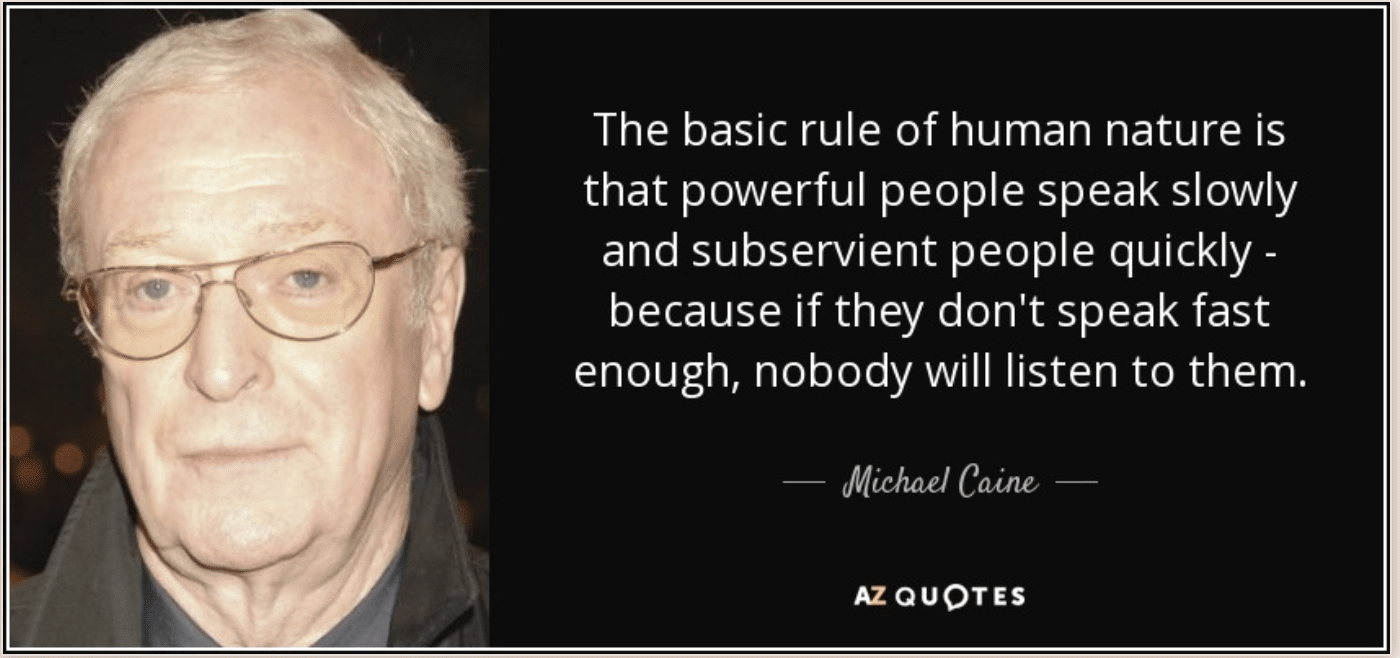

But there’s always a price to be paid for simplicity. Something is lost. Kuznets himself warned that GDP was of limited use as a policy tool because it did not measure the well-being of the workforce or society, and nowadays we might also add that it doesn’t account for increasing inequality, contribution to climate change or environmental degradation.

Despite Kuznets’s warning, the simplicity of GDP meant it became the dominant way to measure and compare economies and to assess the benefit or harm of any policy. Is a motorway good for GDP? What impact will paternity leave have on GDP? And with almost all government policies assessed against the economic output of a country …well that is Kuznets’s Curse. Policymakers targeted one measure above all others.

There is so much written about the limitations of GDP these days that we can expect it to wane in influence over the next 25 years. There was this article in the FT just this week entitled There is more to life and death than GDP. But there are plenty more. Here are a few:

The Guardian 2019: It’s time to end our fixation with GDP and growth

Harvard Business Review in 2019: GDP is not a measure of human well-being

Scientific America in 2020 GDP is the wrong tool for measuring what matters.

The Wire in January 2023 Sorry, GDP. There Are Other Ways to Measure a Nation’s Worth

And it would be remiss of me not to mention Kate Raworth’s 2017 book Doughnut Economics which discusses at length what might replace GDP.

So, while progressives are now counting the cost of Kuznets’s Curse, GDP as a policy-making metric has influenced almost every policymaker globally for almost a century. Its prominence completely eclipsed the person who invented or refined it.

So, what are the wider lessons from this for those of us in the communication game? For me, this demonstrates the power of simplicity. So many I work with are reluctant or unable to simplify. They feel it seems, that it is a little beneath them. So often it is referred to as ‘dumbing down’. And yet simplifying an argument makes it memorable and useable. It can also be a first step or a primer for a deeper understanding. And while we should be mindful of the consequences of simplifying, we should never forget that it is such a powerful ‘tool’.

We should all get better at simplifying.

And I do love a quote, so here are a few on simplicity collected by Margaret Molloy and published on LinkedIn.

“Making the simple complicated is commonplace; making the complicated simple, awesomely simple, that’s creativity.”

Charles Mingus

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

Albert Einstein

“A little simplification would be the first step toward rational living, I think”.

Eleanor Roosevelt

“Simplicity is the keynote of all true elegance.”

Coco Chanel

If you need help codifying and simplifying your organisation’s messaging, give us a call. It is something the Media Coach team can help with. Book one of our message-building sessions and bring along your key stakeholders. Together we will work on a simplified Message House that can be a foundation for your future media, marketing or public affairs engagement. Contact enquires@themediacoach.co.uk or ring us on tel: +44 (0)20 7099 2212.

Secondly, it gives the camera person somewhere to attach your microphone without invading your personal space by fumbling around trying to hide the wire. We don’t really want to see trailing wires on screen and so I sometimes have to explain to a woman wearing a one-piece dress that she is going to have to pass the microphone up through the inside of her dress so that we can hide the cable! This is not ideal. But wear a jacket and I can have the mic attached to you in seconds.

Secondly, it gives the camera person somewhere to attach your microphone without invading your personal space by fumbling around trying to hide the wire. We don’t really want to see trailing wires on screen and so I sometimes have to explain to a woman wearing a one-piece dress that she is going to have to pass the microphone up through the inside of her dress so that we can hide the cable! This is not ideal. But wear a jacket and I can have the mic attached to you in seconds.