The Mick Lynch Style: Not Recommended

Mick Lynch, leader of the RMT, has emerged as one of the most articulate political voices for a generation.

His robust interview style and the confidence to respond witheringly to journalists’ questions are winning him fans in the most unlikely places. Perhaps because people are, in general, fed up with the chatter of the chattering classes.

But while I am dead impressed, I would not recommend this interview to style to others.

Before explaining why, I would like to emphasise a key point that I have not read elsewhere. It is Lynch’s stand-out ability to abstract simple headlines from detail, that is really impressive.

When you hear Lynch speak you think the argument he is making is very simple and straightforward. This is never the case. Behind the scenes Lynch, like every professional, has huge amounts of information, nuance and political – with a small p and a capital P – pressure to navigate. Not to mention lots of numbers to remember: inflation rates, historic pay increases, etc.

His unique talent is to be able to distil everything down to instantly understandable and reasonable-sounding nuggets suitable for the media: ‘This would all be much simpler if the government got round the table’ or ‘We want a guarantee of no compulsory redundancies and then we’ll talk’, etc. It is the simplicity and clarity of his message that is his number one skill.

Second to that, is his ability to come up with a robust response to whatever random or unexpected line the journalist pursues. From ‘Are you a Marxist?’ (Good Morning Britain’s Richard Madeley) to ‘Why do you choose an evil character from Thunderbirds as your Facebook profile picture’ (Piers Morgan). (All the Thunderbirds stuff is 11 minutes into the interview). Or in another interview ‘One doctor says the rail strike is disrupting the treatment of cancer patients, and people will die.’

‘You do come up with some twaddle, Richard.’

‘I can’t believe this line of questioning’

‘We run a picket line. We’ll ask people not to go to work. Do you not know how a picket line works?’

In the Piers Morgan interview there is a great deal of back and forwards about relative pay rates. Morgan asks Lynch – ‘are you a millionaire?’ For example, and then several minutes on comparing Lynch to the aforementioned Thunderbirds character, an evil mastermind wreaking havoc on society. Most comments I saw suggest Lynch came out better in all this.

As a media trainer, I would say Lynch enjoys winding up journalists a little too much. And in each interview, there is a lot more of the trading blows with journalists than there is substance about the RMT case.

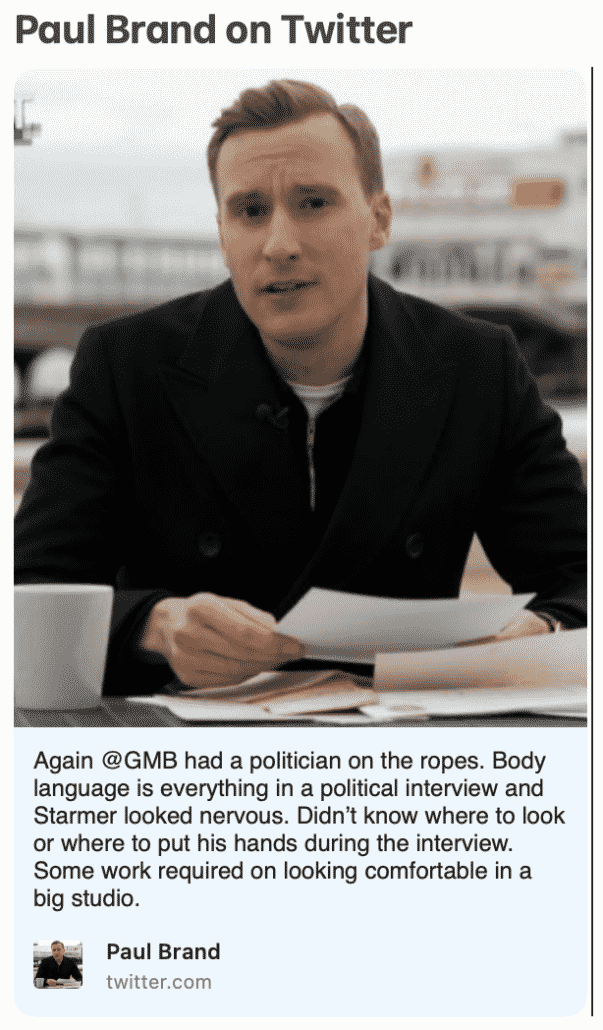

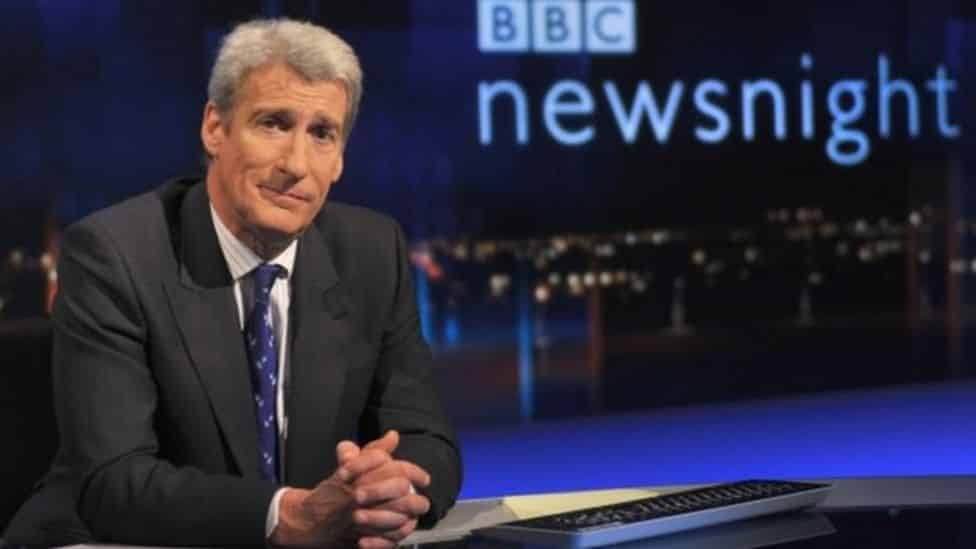

To date, Lynch’s tactics have played well with his audience, but that is not a guaranteed outcome. If you are tempted to call out a journalist for a stupid question, I would think twice. Most people would not be able to do this as effectively as Lynch and journalists love an on-air fight. It’s good for the ratings and remember, live on-air in a studio, broadcasters are in their comfort zone, the interviewee rarely is. From a media training point of view, the danger is too much of the airtime and too much of the attention is on the cat and mouse of the interview, rather than the issues to hand.

So, while this strategy is working for Lynch, I will stick with my advice of not getting into a ping-pong with a journalist on-air, however annoying they are. Keep your cool, respond briefly and dismissively and then get to the point you want to make.

Plenty of others have commented on the Lynch Media Style – and other interviews are cited as evidence. Here is a list of a few of them.

The Mirror … praise of Lynch from Gary Lineker