Stories Leaders Tell

Three things came together in my head this Monday morning:

- On BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme, I heard a BBC reporter talking about ‘weaponising history’. He was referring to the story, or the narrative, President Putin has crafted around why Ukraine needs to be part of a greater Russia.

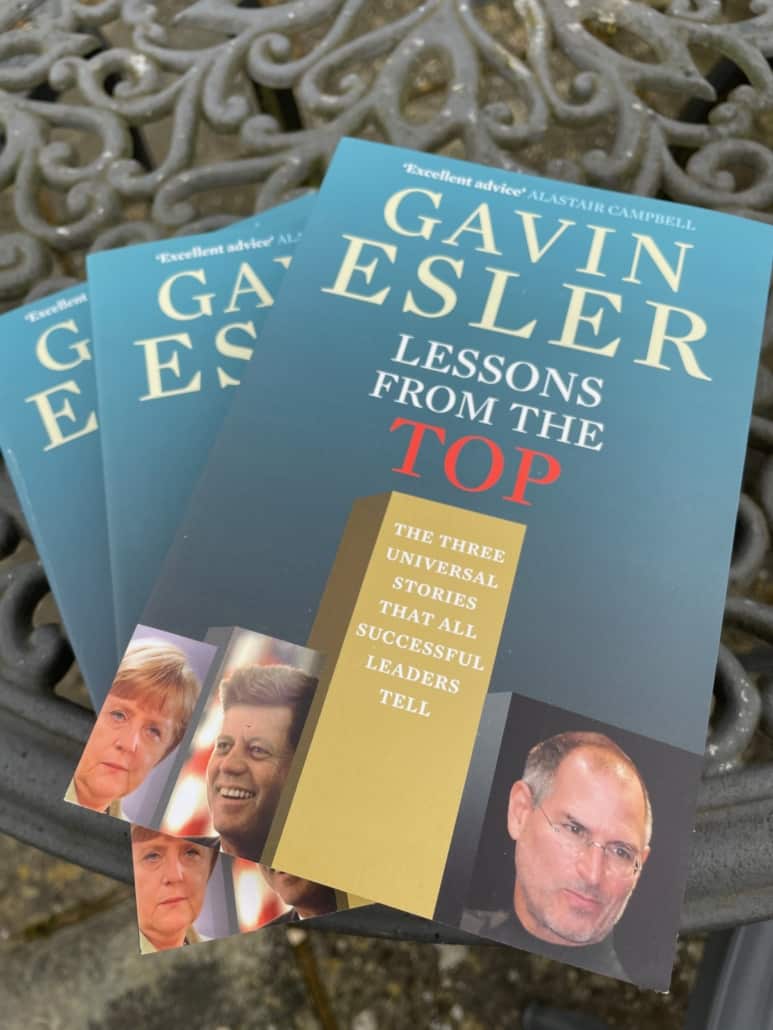

- This reminded me of a very good book by Gavin Esler – Lessons from the Top, Three Universal Stories All Leaders Tell.

- And this directly sparked a previously missed connection with the Public Narrative Training of Harvard Professor, Marshall Ganz, a version of which is sometimes taught by my former colleague, Laura Shields, in Brussels.

Weaponising history is a very interesting phrase. The BBC interviewer, Amol Rajan, was introducing Professor of International Affairs, Nina Khrushcheva from The New School in New York, and together they explored the historical perspective or in other words the ‘stories’ that are motivating Putin and that he is using to justify war, including of course the evidence that Ukrainians and Russian are in fact the same ethnic group. Interview was on BBC Sounds at 8.52am Monday 14th March

‘Weaponising history’ is just a way of saying that a leader is telling a story that motivates, inspires or justifies aggression. Whilst it is a great and emotive phrase, the truth is that we have long understood there is not one version of history. To some extent, all leaders do this all the time.

A leader will create a ‘narrative’ – from selected facts, from half facts or (at worst) from fantasy, that influences others. That is what leadership is all about.

So, while we may hate the message, there is nothing new about the tactic.

One of the interesting challenges is that it is easier to make a compelling story out of great battles, do-or die-dilemmas, moments of decisive action, and so on. All the stuff of action movies. Finding wonderful narratives for peace, reason, not over-reacting, and living peacefully with one’s neighbours, is much harder.

At the time, these ideas were new to me, and I thought the book a great read. I actually bought a dozen copies and gave most of them away.

It was a few years later that my former colleague Laura Shields introduced me to Public Narrative Training – as taught originally, I think, by Marshall Ganz; a left-wing thinker and activist. Funnily enough, his thinking is almost exactly the same – I assume Ganz influenced Esler, but I am not sure.

Anyway, Ganz believes any leader must have three strands to their core narrative. Self, Us and Now.

By the way, if you have worked with me and know how I teach the use of a Message House, you can see that these ideas map straight onto a Message House.

Of course, not all leaders chose to do this. Boris Johnson talks little of himself but a great deal about who ‘we the British’ are. Keir Starmer similarly does not have a powerful story about who he is. Margaret Thatcher did, of course; famously often referring often to her father’s grocery shop. One current British politician who comes to mind is David Lammy MP: a man with a rich heritage of Caribbean ancestry, north London immigrant poverty and English Public School. All laid out in his book Tribes. So, some politicians do and some don’t.

I think those that don’t are missing a trick here.

Working with senior leaders as I do, I often find that this narrative is missing. If I suggest that as an ambitious person he or she should perhaps put some thought into how they tell their personal story and what motivates them, half the time I will be met with resistance. People feel it is ‘not about me’ or ‘I am uncomfortable talking about myself’.

The point for me, is that if people know why you think what you think, they are more likely to trust you.

Hopefully, none of the people I train will use this to justify aggression, hatred or harm.

- Media Savvy Operators Know How to Place a Quote - May 21, 2024

- The Magic of Performance - May 14, 2024

- Our Top Tips: - May 8, 2024

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!