Is There Such a Thing as Voice Privilege?

I was rather taken aback to read an article in the FT this week about ‘voice privilege’. It really annoyed me. Read the article here but as it’s behind a paywall, here is a quick summary.

The author argues that having a nice voice is a huge advantage in life, and Boris Johnson is a prime example of someone who has been successful because of his voice. Janan Ganesh writes:

His voice is beautiful. I don’t mean his accent. I don’t mean his choice of words or his arrangement of them: what is called “eloquence”. I mean his voice. Deep and textured, raspy without crossing into sibilance, I can see (or hear) why people want to be around it. And why those cursed with a squeak or a murmur go through life hamstrung?

Why is this annoying? Because, as is so often the case, there is an element of truth in this, but it is grossly exaggerated.

And as a presentation trainer, worrying about the beauty of someone’s voice is not top of my list of things to work on.

Some people, it is true, naturally have lovely voices. For a variety of reasons that boil down to luck: social class, school, parents, ethnicity, etc. And as you would expect, some have voices that lack authority, are too squeaky, or too quiet to be instantly attractive.

But this is true surely about everything in life. Some have lovely hair, some bad teeth, some are born into money while others have a natural ability to connect with people. All of us have a share of both positive and negative.

As someone who coaches public speakers, I would say, use what you are lucky to have and work to improve that which you don’t like. But don’t get too hung up on it because, actually your audience will judge you on many things, not just something as superficial as your voice.

As humans, we do make snap judgements and have unconscious biases as Ganesh argues, but we also do a very good job at overcoming those biases, once we have more exposure to someone or their ideas.

There isn’t one hidden trait that will make you a great speaker against all the odds just as there isn’t one advantage in life that will ensure you get to the top, whatever that means.

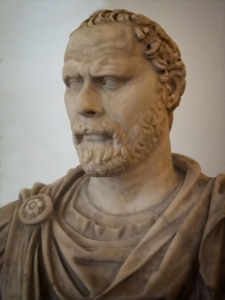

Demosthenes

The crucial thing that will make you a successful speaker is working on it. The evidence is that all successful orators worked on their communication skills. Churchill famously battled with public speaking and a natural lisp. We recently learnt that Joe Biden has always battled with his stutter. A Greek statesman, Demosthenes famously overcame his speech impediment by speaking with pebbles in his mouth. Warren Buffet was terrified of public speaking. The list goes on.

The biggest handicap you can have in this area is to think nothing can be changed. If you believe that you are the way you are and that’s your lot, you will probably be proved right.

In my experience as a professional coach, most of us underestimate our ability to adapt and change. Neural plasticity is the scientific term. We all have the ability to adapt and modify our voice, amongst all the other things we can modify if we decide to.

And as presentation coaches (as well as media trainers) we see this every day. Coaching helps a client to focus on what matters to them. Working with a video camera, recording and playing back presentations or interviews, we can make people aware of the unconscious behaviours that can then be tackled. People can lower their voices, they can slow down, they can become more animated, they can learn to articulate more clearly.

The second handicap is to believe your fellow human beings, your audience, will never be able to see past your less-than-perfect pitch. They won’t make allowances for your nerves, they won’t take you seriously because you are short, or bald or overweight or you have a light voice. But it is just not true.

If you have interesting things to say, and you care about communicating them clearly, audiences will listen. It just takes a bit of effort.

Further reading:

Analysis of Oprah Winfrey’s speech

- Media Savvy Operators Know How to Place a Quote - May 21, 2024

- The Magic of Performance - May 14, 2024

- Our Top Tips: - May 8, 2024

Lindsay, hi.

I’m surprised that the importance of voice was slightly below you radar. Two points – one personal, one more of a business nature. The personal point is that one of my reasons to quit smoking was I realised that a good third of my work time consisted of talking to people on the telephone. The light dawned when I came home one evening and replayed a message I’d left on my own answer machine: a weak voice, punctuated by throat clearing and thus hesitant. That gave me a good reason to quit, and when I did, it was noticed by many of thiose i spoke to on the phone regularly. The second point is from a business perspective, and it is best made by my former QVC colleague Jon Briggs, who is now the voice of Siri in the UK.

Well I pleased you gave up smoking for whatever reason! Eric below does a lot of voice training but I think we take the view (as does John Briggs) that while nature and nurture play a part, there is a lot we can do to improve what luck has given you. Hope you are well.

I have to say, I agree with Lindsay; the article annoyed me too.

For three reasons.

Firstly, Janan Ganesh seems to think that positive or negative perception of other people’s voices is universally held. For example, he says of Boris Johnson that “His voice is beautiful”. Really? To everybody? Without exception? A quick poll around four of us in the office – and not one of us would agree. (Granted, this is not a huge sample size, but it’s quadruple that of the author on his own). This doesn’t make Ganesh’s assertion wrong, of course – it’s his (perfectly valid) opinion – but it is worth pointing out that not everyone shares it. And if not everyone shares a view about a particular voice, it’s hard to see how it can be considered automatically ‘privileged’; it will depend on who is in the audience.

Secondly, adding ‘voice privilege’ to the list of ways of dividing the world into group identities doesn’t really help. As Lindsay mentions in her blog: “Some have lovely hair, some bad teeth, some are born into money while others have a natural ability to connect with people.” So, besides skin colour, gender and sexuality, does this mean we should make further division by these attributes too? If so, what about athleticism, educational background, age, weight, height, quality of eyesight, physical attractiveness, emotional resilience, family structure, friendship groups, wealth, dress sense and the rest? You’d be hard pushed to claim that some of these categories don’t, if anything, have an even greater impact on the way we’re perceived.

Under this theory, would a speaker with a beautiful voice from a poor, working-class family be more ‘privileged’ than a speaker with a dreadful voice who was privately educated? What if either one of them was blind? Or had no charisma? Or bad breath? How would you judge their respective ‘privileges’ then? The question is so bizarre as to be laughable.

The truth is that each of us lies at a unique nexus of all these traits and more – which is what makes us individuals. And I don’t want to hear a speaker talking on ‘behalf’ of a group; I want to hear a speaker talking about subjects as they see them – which may, or may not, align with others in any given sub-set.

Finally, and most importantly, it suggests that those without so-called ‘voice privilege’ are cast aside. They are placed very firmly in a corner as ‘victims’ (of a society that puts more value on styles of voices other than their own). In his article, Ganesh says that in meetings he sees “perceptive mumblers lose out to sonorous mediocrities”. Yes, me too. But surely we want to change that? And the best way to do so would be to recognise that any speaker can have an impact by having interesting things to say and communicating them with clarity and confidence. And certainly not buy-in to the dangerous view that some speakers are somehow more ‘valid’ than others.

That’s what I’ve set out to do in 35 years of voice training. And I’m not going to let some concocted theory about ‘voice privilege’ change that now.

There is a follow up to the FT article from Emma Beddington in The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/feb/26/talking-posh-still-pays-thats-why-boris-johnson-is-rolling-in-it

I am not sure it adds much to the debate but it is funny.